Individuals and institutions alike are allocating more of their dollars to investment strategies that meet some level of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) criteria. This is commonly referred to as “responsible,” “sustainable,” or “green” investing. I’ll use the term sustainable.

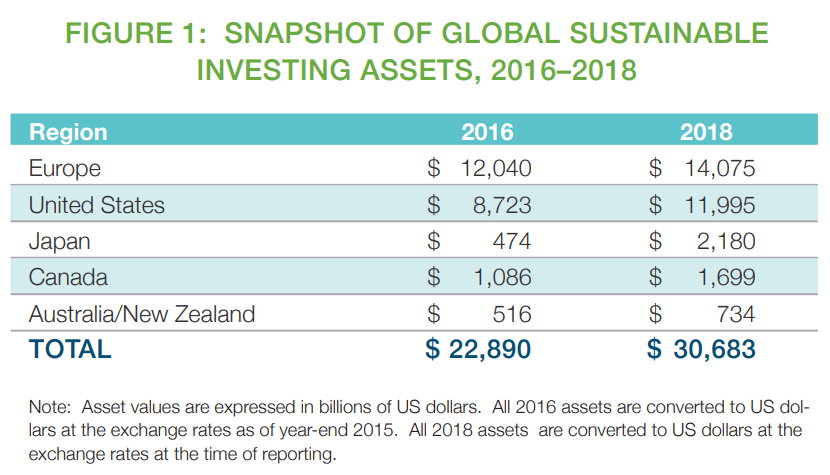

Call it what you will, according to the 2018 Global Sustainable Investment Review, more than 25% of US domiciled assets under management were invested in sustainable strategies at the start of 2018. In Canada it is just over 50%, at $2.1 trillion CAD ($1.7 trillion U.S.). That’s up 42% since 2016. BlackRock, one of the world’s largest asset managers, recently committed to making sustainability a key part of their investment process.

Source: Global Sustainable Investment Alliance

This growth in sustainable investing is good news if it leads to positive social impact. But it also has important implications for expected investment outcomes. There are a growing number of ways to better align your investments with your views and values. But be it known: It’s probably going to cost you.

Two of the most common types of sustainable investment strategies are negative screening and ESG integration. Negative screening eliminates certain sectors, companies, or practices from a portfolio. ESG integration is more of a reweighting. Instead of completely eliminating industries, an integration strategy will underweight companies with lower ESG scores and increase the weight of companies with higher ESG scores. There are index funds that employ each of these strategies individually or in combination.

Having a sustainable portfolio may sound like a good idea. It might feel even better. However, I think you need to consider two equally important questions when investing sustainably:

I suggest assessing both in tandem. Consider the following scenarios, and how you might feel about each.

Only you know what balance is acceptable for your investments. But to help you think through these and similar trade-offs, let’s look at some of the research.

Let’s start with the impact of socially responsible investing on expected returns. Rocco Ciciretti, Ambrogio Dalo, and Lemmertjan Dam examined the effect of ESG scores on stock returns in a 2019 paper. They controlled for common risk factors and looked at a global sample of 5,972 firms from 2004–2018. They found that companies with higher ESG scores tended to deliver lower average returns than companies with lower ESG scores.

They found a statistically significant negative premium for the ESG characteristic in a traditional Fama/French five-factor regression, a six-factor regression including momentum, and a seven-factor regression including an ESG risk factor. They associated a one standard deviation decrease in the ESG score with a 0.13% increase in monthly expected returns.

Put simply, after controlling for exposure to known drivers of returns, companies with higher ESG scores tended to do worse than companies with lower ESG scores.

The authors considered two possible explanations, both grounded in economic theory:

Based on the previously mentioned factor regressions, the authors found it much more likely that investor preference drives the negative premium. Investors may be willing to accept lower expected returns simply because they do not want to invest in certain types of firms. This is not a risk premium, but an effect based on investor tastes.

That word, “tastes,” is important.

In their 2007 paper, “Disagreements, Tastes, and Asset Prices,” Eugene Fama and Ken French explained that investors who have a taste for an asset may hold it partially as a consumption good, regardless of its expected return profile. The effect on prices could be meaningful when enough wealth is controlled by investors with specific tastes, such as a sustainable investor’s preference for companies with higher ESG scores.

Here’s another way to think about it:

In a 2019 study, Olivier David Zerbib developed an asset pricing model including premiums for ESG exclusion and investor tastes. He related the exclusion premium to the increased risk of stocks that are neglected by sustainable investors. He related the investor taste premium to the cost sustainable investors incur when they internalize that which they believe will maximize their welfare, instead of the market value of their investments.

Using this model, Zerbib analyzed U.S. stock data from 2000–2018. He found an exclusion effect of 2.5% per year, and a taste effect of 1.5% per year. Over the time period examined, these effects show the approximate magnitude of underperformance driven respectively by a negative screen, and an integrated approach to a sustainable portfolio.

As ESG preferences grow stronger, we expect these pricing effects will become more pronounced. In a 2019 paper, Lubos Pastor, Robert Stambaugh, and Lucian Taylor constructed a theoretical model to examine the implications of ESG investing on expected returns. They found:

Think about it this way: What if everyone shared the same tastes, including a preference for the same ESG characteristics, the same willingness to invest in “bad” companies with higher expected returns, and the same acceptance of “good” companies despite their lower expected returns?

If that were the case, everyone would hold the market portfolio and be happy; there would be no ESG investing industry. If there are two groups – one with no ESG preferences, and one with strong ESG preferences – then there is an ESG investing industry. As this dispersion in ESG preferences grows, the ESG investing industry gets bigger and more popular. In aggregate, expected returns for sustainable portfolios get lower.

Pastor, Stambaugh, and Taylor also found that sustainable investing leads to positive social impact by encouraging sustainable firms to invest more, while discouraging unsustainable firms from investing. The latter is due to the effects of investor preferences on their cost of capital.

Let’s recap. Yes, you can encourage change in the world by investing in companies that meet ESG criteria. But as long as there is ESG preference dispersion, you are doing so at the expense of lower expected returns. This joint effect must be true. If sustainable investing works the way it is supposed to (by putting pressure on unsustainable companies), the firms excluded from sustainable portfolios must have higher expected returns. Sustainable investors must have lower expected returns than the preference-free market.

I think we have established that investors should expect lower risk-adjusted returns from a sustainable portfolio. Plus, a portfolio with a negative screen that entirely eliminates industries will tend to reduce expected returns even more than a portfolio that reweights companies based on their ESG score.

But lower expected returns are not the end of the story. There are a couple more trade-offs to consider.

So, investing sustainably entails lower expected returns, less diversification, and higher fees. These costs exist on a continuum. The more sustainable you want to get, the higher these costs tend to be.

If we start on the low-cost end of the spectrum, we might have iShares Core S&P/TSX Capped Composite Index ETF (XIC), with no ESG filter. XIC is market-cap weighted, with 235 holdings, and a 0.06% expense ratio. It will almost certainly deliver market returns after costs.

One notch up, there’s the iShares ESG MSCI Canada Index ETF (XESG), which favours companies with high ESG scores. It has 129 holdings and an expense ratio of 0.22%. MSCI has designed the index to have an expected 1% tracking error, so expect market return, plus or minus a random error.

For more sustainability, we would need to increase the tracking error budget, and expect still higher fees. For example, the Desjardins RI Canada – Low CO2 Index ETF (DRMC) has 63 holdings, more exclusions, and stricter ESG criteria. It has an expense ratio of 0.29%.

As we move along this continuum, the higher costs might be worth it, if the results increasingly reflect your beliefs. But this is one of the biggest problems sustainable investors face: While a fund may be “ESG”, “green”, or “sustainable” in name, how well does it really align with your beliefs in practice?

Even the rating agencies that determine the ESG scores don’t always agree on the definitions. Florian Berg, Julian Kölbel, and Roberto Rigobon explored this in their 2019 paper.

They looked at ratings from five prominent ESG rating agencies, and found their ratings had an average correlation of 0.61, with a range between 0.42–0.73. (For context, credit ratings from Moody’s vs. Standard and Poor’s are correlated at 0.99.) The authors found the disagreement is driven nearly equally by differences in ESG definitions, and how those definitions are measured.

We can look at the MSCI Canada IMI Extended ESG Focus Index as an example. This index takes an integration approach, combined with total exclusions for tobacco, controversial weapons, companies that produce or have ties with civilian firearms, and businesses involved in severe controversies. All good things to avoid for a socially conscious investor. But, here’s an issue: One of its largest holdings is Suncor, a Canadian energy company specializing in synthetic crude production from oil sands. More than 16% of the index is made up of energy companies.

FTSE, another index provider, creates ESG indexes that exclude oil, gas, and coal companies. They don’t exclude downstream companies like pipelines, but it’s still a step in the right direction for many sustainable investors.

Inconsistent ratings should not be a surprise. From the Berg, Kölbel, and Rigobon paper, we can see that the energy category is a major point of disagreement across ESG rating agencies, with an average rating correlation of only 0.29.

The inclusion or exclusion of oil and gas companies in an ESG index is only one example of a larger problem. Name your social or environmental issue of choice, and different index providers are likely to treat it differently. Similarly, if an index provider treats one issue the way you would hope, they might not align with your views on other issues.

This is a big problem from two perspectives: First, you might end up enduring the higher costs of a sustainable portfolio while owning companies that conflict with your values. Second, companies might be confused about which actions they need to take to improve their ESG performance.

If you’d like to invest sustainably, the approach you take calls for precisely managing the trade-offs between implicit and explicit costs, versus your specific set of beliefs. The perfect portfolio for your views and values could end up being too under-diversified, too expensive, or otherwise impractical. On the other hand, the simplest, cheapest, and most diversified portfolio is likely to conflict a little, or a lot, with the views and values of most sustainable investors. So …

I have one last thing to add. It is true that more sustainable companies have lower risk-adjusted returns than less-sustainable companies. But comparing an ESG index fund to a total market index fund is not really a fair comparison. ESG indexes tend to have positive exposure to some of the factors that explain differences in returns between diversified portfolios. However, this is a subject for another time. So, keep an eye on these Common Sense Investing posts, and tune in weekly for episodes of the Rational Reminder Podcast wherever you get your podcasts.