When talking about saving for retirement, most people default to the common 10 or 15 percent of income towards retirement. But are those numbers accurate and is this a reasonable approach?

The traditional way planners talk about savings is to take a certain percentage of your income and save that towards retirement each and every year. As your income and standard of living increases, so will your savings. This translates into something like savings of 10% to 15% of your income earmarked for retirement. Unfortunately, unless you’re currently 25 and diligently saving that 10% for retirement each year on top of any other savings like for a house down payment, or you started at 25 and have kept up that savings rate for retirement, I’m not convinced that a 10% savings rate will be sufficient to cover your retirement income.

The other way to look at things is to consider the typical life cycle. Life and it’s associated expenses are very often quite lumpy so the 10% of income towards retirement might not work very well. However broad life phases can generally fit into the following framework: you finish high school and start working or go to college/university. You might still be living like a student with parents or with roommates and your bills and responsibilities are relatively low. While your income might be lower at this point in your career, so are your expenses. You can use this opportunity to save aggressively, for retirement and/or other goals like a house down payment. The next phase is the sandwich phase. This is when you’re starting a family, buying your first home or moving to a larger home, and potentially have parents to support. While income might be growing at this point in your career, one parent might be taking time off work, child expenses are high, mortgage payments are high, etc. You’re squeezed and just trying to stay out of debt or might be more focused on putting money away for children’s education. Your ability to save for retirement might be limited and savings are reduced or put on the back burner. Finally, when children have left home, and you are hopefully at the peak of your career and perhaps your mortgage has been paid off, you’ve got a huge ability to save for retirement.

If you set aside a larger amount of savings when you were younger, this puts less pressure on you in the sandwich phase and right before retirement since those early savings might have had 30 to 40 years to grow prior to retirement, with another 30 years throughout retirement. This can be viewed as a barbell approach to saving.

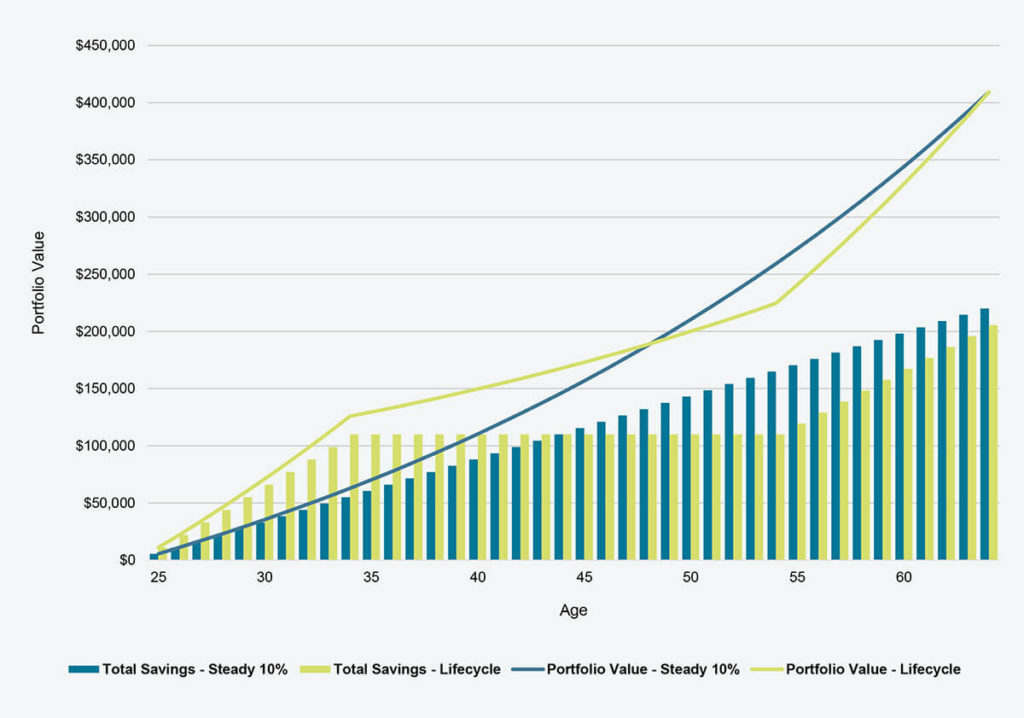

Let’s take a couple very basic examples. The first is the scenario where you start early, at age 25 and save 10% of your pre-tax income of $55,000. After 40 years, the portfolio has grown to $409,000 at a 5% pre-inflation growth rate, or a 3% real return. The second scenario follows along with the typical life cycle. While expenses are lower, you save 20% of your pre-tax income starting at age 25 until age 35. Then between ages 35 and 55, while you’re squeezed by mortgages, kids, and elderly parents, you don’t save anything towards retirement. In order to hit the same portfolio value after 40 years, you need to save 17% of your income between ages 55 and 65. The total amount you save in the second scenario is slightly less, because you front loaded half of your savings and it had a longer time to compound and earn a return.

If you were busy paying off debt and saving for a house down payment prior to age 35, didn’t save anything due to the high costs associated with being part of generation squeeze, any only started saving at age 55 once the major costs of life fell off, you’d have to save 65% of your income to accumulate the same amount of assets! This is assuming your income keeps pace with inflation starting at age 25 which might be too conservative, but it still shows that you must save much more if you start late compared to starting early.

If you start at age 30, the steady annual savings rate needed to accumulate an equivalent portfolio bumps up to 12%, compared to 10% at age 25, and if you waited until 40, it jumps to 21% of pre-tax income.

If your income is low, your savings rate doesn’t need to be as high, since government benefits will account for a higher proportion of your retirement income. If you work longer, your regular savings continue longer, your portfolio can grow more as a result of being invested longer, and you don’t need as much accumulated because your retirement period will be shorter.

As you can see, the savings rate necessary will really depend on your individual situation (how old you are, what your income is, how long you plan on working, your investment return, etc.) and what retirement incomes and assets are available to you, so doing some projections is really the only way to figure out what your savings rate needs to be, whether that’s 10%, 20%, higher or lower. The lifecycle outlined above may not apply to you. Maybe you remain single, maybe you don’t have children, maybe you continue renting throughout life. Financial projections can account for increased costs and the drop in savings that will result during certain periods of your life, whatever your situation, to make sure you’re on track to hit your retirement goals. In order to figure out what your savings rate needs to be, you need to figure out what your retirement might look like (and when), then work backwards from there. How much do you need to accumulate to make that retirement income happen, and how much do you need to save now and in the future to get there? In the coming weeks, I’ll be outlining in more detail the various components of financial projections, to help you start to piece together what you need to consider when determining a savings rate. As I’ve outlined in today’s video, if you can start saving even a little bit now, that will help take off some of the burden of future you.