The core foundational elements of a financial plan are assumptions, which are the best approximations of what the future will look like. Assumptions can range from a single number, such as a retirement date, to more complex projections, such as the distribution of expected future stock market returns.

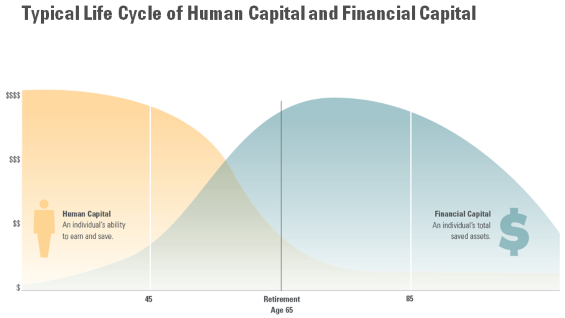

The average young Canadian will have most of their wealth tied up in their human capital. Human capital is the ability to convert skills, time and labour into financial capital, or the ability to earn income. A comprehensive financial plan will detail the transition of wealth from human capital to financial capital as time to retirement decreases and investments/savings increase.

Human capital is made up of lifetime earnings and the risk of those earnings. It cannot be objectively valued in the same way a bank balance or salary could. In your typical financial planning software, a financial planner will input today’s pre-tax earnings growing at a defined rate to reflect a change in those earnings over time.

Very few of us expect to be making the same income throughout our careers. As we put in more hours, we develop new skills and become more valuable to our employer or the marketplace. Given our increase in value with age and experience, what income growth rate should we use in financial plans? If the ability to earn an income determines most of a young Canadian’s wealth, then the growth rate of that income over time will be a critical assumption in their financial plan.

The simplest and most conservative starting point is assuming that wages increase in line with inflation. If this were true, Canadians would consume roughly the same amount throughout lifetime as their raises move in lock-step with the increases in prices of the goods around them. When we compare the salaries and consumption habits of more experienced employees to their rookie peers, we can see this is not the case.

FP Canada uses a grossed-up value from the CPP/QPP actuarial calculations (0.9% and 0.8%) and therefore recommends inflation + 1%.

A planner with a more aggressive approach or a client with greater flexibility may wish to use a more realistic estimate. An overly conservative assumption will short-change today’s consumption and lead to over-saving. Rather than rely on industry standards, this analysis will pull from historical data and future projections and use a build-up method to calculate a more appropriate estimate for the expected change in income as Canadians age.

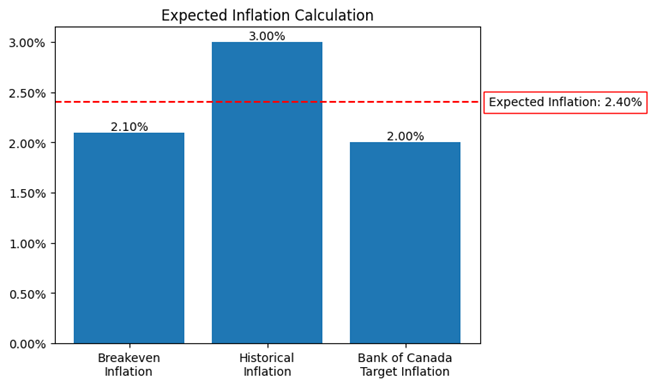

Inflation is the rising price level of all goods and services, including employee labour. Inflation to an employer is a cost-of-living adjustment to an employee. Our PWL Financial Planning Assumptions define long-run Canadian inflation as the average of historical inflation, the Bank of Canada’s inflation target, and 30-year Government of Canada bond breakeven inflation.

A one-third weighting on each of the above gives us forward-looking inflation expectations of 2.4% per year. This will be the first step in our build-up of expected income increases over time.

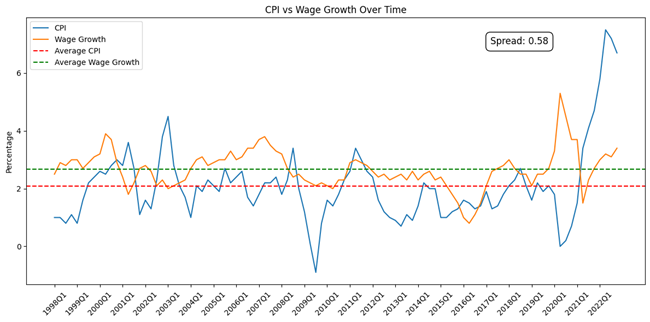

It is easy enough to assume that inflation and wages grow at the same rate but historically this has not been true. If we compare the change in the Consumer Price Index (inflation) to the change in the Year’s Maximum Pensionable Earnings (wages) since 1998, we see that wage growth has been nearly .6% higher than inflation per year, on average.

Interestingly, inflation has no predictive power when it comes to forecasting wage growth. You cannot assume that, for example, “since inflation was high last year wage growth will be high the next”. However, the difference between the two is statistically significant and will be the second level in building up our expected increases in income moving forward. So far, our assumption is:

2.4% (expected inflation) + .6% (expected wage growth over inflation) = 3%

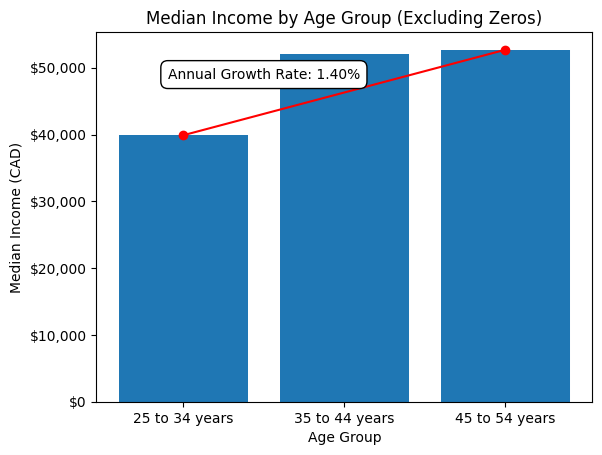

Who commands a higher salary? A novice pilot on their first flight, or a seasoned 55-year-old veteran? A nurse on day one or a nurse who has seen it all? Even without a change in title, experience has value. To estimate what the value of one additional year in the trenches is worth, we used Statistics Canada data from 2020 comparing median income by age:

If we assume that the median 25 to 34 year old maintains their median ranking relative to peers into their 50s, this gives us an average per year increase of 1.4% above any increases from inflation or aggregate wage growth. This extra income is an Age/Experience credit based on the increased value of the wage-earner.

Notably, the increase is much greater in the first 10 years than the second. Assuming a linear increase over 20 years is more conservative than assuming two employment periods: one of rapid income increases followed by another at a more modest pace.

To sum it up, we’ve built an expectation for income increase using three factors. The expected inflation of 2.4%, expected wage growth over inflation at .6%, and what we’re calling an “age/experience credit” of 1.4%. Adding these together, we get an expected yearly income increase of 4.4%.

This is 2% higher than expected inflation and 1% higher than the recommended guidelines from FP Canada. Using lower numbers will understate the value of human capital in a financial plan. Lower wage growth rates will add a safety buffer when running planning projections to determine sustainable spending and target retirement dates but may also lead to over saving in the early years.

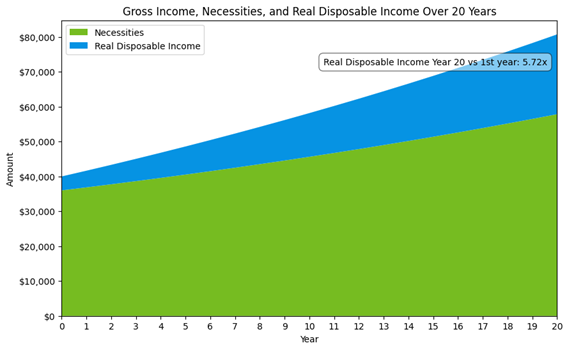

Comparing 2.4% with 4.4% may sound like splitting hairs, but it is important to recognize that 4.4% represents an 83% faster growth in total income. This is not at all something to ignore! If we look at the increase in disposable income over time, these numbers are even more dramatic.

Assume that 90% of a 30-year-old’s $40,000/year income goes to the basic necessities of life: groceries, gas, rent, etc. If $36,000 goes to expenses, they start out with only $4,000 a year of disposable (fun) income. If necessities increase with inflation but wages increase at a rate of inflation plus 2%, progressively more of that income can be allocated to discretionary, non-essential expenses each year. This is much more in line with the spending habits we see in practice, too.

Projecting forward 20 years, we see a 572% increase in real (after inflation) disposable income!

As Canadians age, less and less of their income goes toward the bare minimums and more can go toward spending on things they enjoy. This could be upgraded necessities: a nicer house, or better food. Alternatively, it could be new additions to their lifestyle: vacations, entertainment, or charity. In our example, this discretionary spending increases from $4,000 a year at 30 to over $22,000 per year at age 50 (increasing taxes omitted for simplicity).

While 2% may not seem substantial, a near 6-fold increase in discretionary spending certainly does. Realistic projections of income changes through time and the effects of those changes on discretionary spending will help financial planners develop better projections and help clients make better financial decisions.

This is not a call to base all income projections on a 2% above inflation annual increase in income. Just as we wouldn’t project a 10% annual return in a financial plan based solely on select markets’ historical performance, we also wouldn’t assume the future will precisely mirror the past. Safety margins are important.

This analysis highlights important considerations when building and reviewing a financial plan: