Global diversification is one of the keys to a well-constructed portfolio. We have known this for a long time – and investors have been largely ignoring it for just as long.

In their 1991 paper, Investor Diversification and International Equity Markets, Ken French and James Poterba documented investors’ preference for owning stocks from their home country, commonly known as home country bias. They found investors preferred domestic stocks because they expected higher returns in their own equity market compared to other countries’ markets.

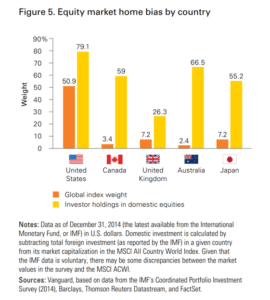

When they wrote their paper, French and Poterba also found that investors’ portfolios consisted of 80–98% domestic stocks, depending on the country. Today things have gotten better. That is, investors are often more globally diversified than before. But they still have a strong preference for their own country’s stocks.

Is that so wrong? Today, I am going to explain why a little bit of home country bias may not be such a bad thing.

In 2017, Vanguard published a paper entitled, The global case for strategic asset allocation and an examination of home bias. In it, they documented the extent of home bias in several countries, including Canada. They found, while the Canadian market makes up just over 3% of the global stock market capitalization, Canadian investors held closer to 60% of their equity portfolios in Canadian stocks.

There are strong, logical arguments in favour of building a globally diversified portfolio. To name a few:

Market Cap Weights and Measures

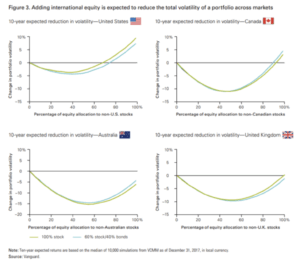

So, the amount of global diversification matters. But to what extent? We don’t necessarily need to follow market cap weights to get the full benefits of global diversification. In terms of volatility reduction, Vanguard found that the maximum expected volatility reduction was achieved when a Canadian investor allocated 50%–60% of their equity portfolio to non-Canadian stocks. Allocating more than that actually increased volatility.

In other words, there is definitely an incremental benefit to adding non-Canadian stocks to a Canadian portfolio. But, from an expected volatility perspective, the marginal benefit of adding non-Canadian stocks declines quickly beyond a 60% allocation. Vanguard found similar results for other countries.

That said, modelling expected volatility is not the only thing to think about when building a portfolio. Plus, it’s always dangerous to rely too heavily on models, because future outcomes are uncertain. But we can see that using market cap percentages alone for geographic allocations is not necessarily the best way to reduce volatility for an investor in a given country.

So far, we have seen that global diversification is important, but the benefits from a volatility reduction perspective can be achieved while still maintaining a substantial home country bias. Remember, market-cap weights would suggest Canadian investors only allocate roughly 3% to Canadian stocks, which would be sub-optimal based on Vanguard’s expected volatility analysis.

The concept of home bias gets more interesting when we start thinking about some of the other factors that impact investment outcomes. Minimizing volatility and gaining long-term access to foreign economies are good things, but real-life investors also need to think about costs, taxes, and their own behaviour.

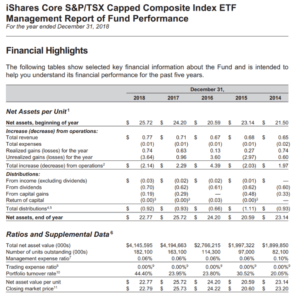

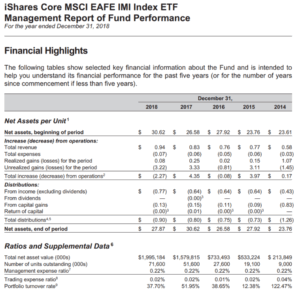

The cost of index ETFs has continuously fallen in recent history, to the point that investing is almost free in terms of management expense ratios. A Canadian investor can buy a Canadian stock ETF like the iShares Core S&P/TSX Capped Composite Index ETF (XIC) for a management expense ratio of 0.06%. They can buy its U.S. counterpart like the iShares Core S&P U.S. Total Market Index ETF (XUU) for a management expense ratio of 0.07%. When we get outside of North America, the fees do get higher. An ETF of international developed market stocks like the iShares Core MSCI EAFE IMI Index ETF (XEF), has a much higher expense ratio at 0.22%. The emerging markets ETF, iShares Core MSCI Emerging Markets IMI Index ETF (XEC), is even more expensive at 0.26%.

Fees are important, but taxes are an even bigger consideration. Canadian public companies generally distribute eligible dividends. An eligible Canadian dividend received by a Canadian taxpayer is taxed more favourably than a foreign dividend in a taxable investment account. In 2019, at the highest marginal tax rate in Ontario, an eligible dividend is taxed at 39.34% after the gross-up and dividend tax credit are considered. A foreign dividend is taxed as regular income at a rate of 53.53%. This is a meaningful difference for a taxable investor.

Even if you are investing in tax-advantaged accounts like an RRSP or TFSA, there is a meaningful tax cost to owning foreign securities. When a dividend is paid to a foreign asset owner, there is generally a withholding tax applied. The U.S. withholds 15% of any dividend paid to a Canadian asset owner. In a taxable investment account, this foreign withholding tax is recoverable; it can be used to offset your Canadian taxes. In a registered account, this foreign withholding tax is not recoverable.

What are the costs involved? To illustrate, when a foreign security is held in an RRSP account or a TFSA:

Some of these unrecoverable foreign withholding tax costs can be reduced or eliminated by holding U.S.-listed ETFs in an RRSP account; the United States does not apply foreign withholding tax on assets held specifically in an RRSP account. But this solution introduces the added complexity of converting currency to purchase U.S.-listed ETFs, which is not attractive to many investors. If you own a Canadian-listed asset allocation ETF, like the iShares Core Equity ETF Portfolio (XEQT), you cannot take advantage of this nuance, because XEQT is a Canadian-listed ETF.

It is very important to understand, this is not such a bad thing. You don’t have to run out to sell XEQT and buy the underlying U.S.-listed ETFs in your RRSP just to reduce your foreign withholding taxes. The point is, in both taxable and non-taxable accounts, owning non-Canadian stocks comes with an added level of tax cost. This means there is little question that Canadian stocks are more tax-efficient than non-Canadian stocks.

That was a bit of a tax digression, but it is important. Investing outside of Canada comes with higher costs and taxes for a Canadian investor. If we are thinking about our optimal geographic allocations, we might have started at market cap weights to diversify our exposure to global economies. Then we might have increased our allocation to Canadian equities based on the Vanguard mean-variance analysis. Now, with the extra information on costs and taxes, we might nudge that Canadian equity allocation a little higher still.

Another thing I often hear about investing in Canada is that the market is poorly diversified, with too much invested in energy and financials. This is true. But the rest of the world is relatively light on these sectors, so loading up on Canadian stocks beyond their market cap weight does not necessarily result in a concerning level of sector exposure in your portfolio.

Costs and taxes aside, Canadian investors are faced with a major behavioural challenge in the form of home country bias. That is, we are in Canada. The Canadian stock market is in our faces every day. If the Swedish stock market goes on a bull run, we Canadians won’t notice, but if the Canadian stock market is on a tear, we can’t ignore it.

Knowing we have the same behavioural tendencies any other investor has – including home country bias – there is a meaningful risk that Canadian investors owning Canada’s 3% market cap weight would feel the urge to increase that allocation when the Canadian stock market is doing well. The result is a classic case of buying high.

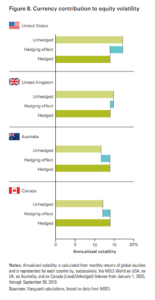

One aspect of the geographic allocation decision that does not carry much weight is currency. Some people may feel that foreign currency exposure increases the risk of their portfolio. But Vanguard’s analysis found currency contributed only a very small amount to the overall volatility effects of diversifying outside of Canada.

Other studies have found currency exposure can increase or decrease portfolio volatility, depending on the time period. In equities, currency volatility ends up being similar in magnitude to equity volatility, while being imperfectly correlated. Thus, it potentially offers a diversification benefit. If you felt strongly about currency exposure, you could hedge it. But In short, currency does not play a meaningful role in the home bias decision.

How much home bias is optimal? Based on these factors there are trade-offs to think about. We know that global diversification is important, but too much diversification might actually increase portfolio volatility (at least based on Vanguard’s model). We also know fees and taxes make the cost of investing outside of Canada a bit higher than investing in Canada. Moreover, from a behavioural perspective, it might feel bad to own too few Canadian stocks when the Canadian stock market is doing well.

Understanding these trade-offs, it is not obvious exactly how much home bias is optimal, but I would argue that a degree is acceptable, if not desirable. With no easy answer about geographic allocation, following a simple, even split across Canadian, U.S., and International stocks is probably a sensible solution. This is how the Vanguard asset allocation ETFs like VEQT are approaching it. If that solution is good enough for them, perhaps you will conclude it will also work for you.