In many walks of life, it is possible to have too much of a good thing. What about in your portfolio? Every so often, I hear someone argue that investing in index funds can leave you over-diversified. The logic goes something like this: Instead of buying all of the companies in an index, you could buy a subset of only the “good” ones, to potentially outperform the index as a whole.

It’s a tempting proposition. Of course, you cannot beat the market by simply holding it, so why not try to do better than that? The problem is, by decreasing diversification, you not only increase your range of possible investment outcomes, you also end up with a disproportionately large probability of having a negative outcome relative to the market.

In other words, the less you diversify, the more likely you won’t even break even. This has to do with something called dispersion and it explains why index funds do not lead to an undesirable over-diversification. Would you like to see how this works? Keep reading.

For our purposes, dispersion is the size of the range of returns observed for an investment strategy. if an investment strategy has high dispersion, we would expect the actual result realized by an investor over a given time period to fall across a wider range of possible outcomes – both above and below the expected value.

Another way to think about high dispersion is that your outcome is less reliable. Even if you have good reason to expect some amount of average long-term return, high dispersion means you are less likely to get it. On the other hand, low dispersion means your actual result is more likely to be closer to what you expected.

Now, if your goal is to seek massive gains by successfully picking stocks, then you want high dispersion. While this doesn’t mean you are going to succeed, it gives you a fighting chance. But, you must also accept the potential for massive losses. With high dispersion, you increase your odds for either extreme.

For any long-term investor (anyone hoping to optimize their odds for meeting their personal financial goals) a low dispersion of outcomes is much more favourable. You’re not going to hit the jackpot, but your diversified index fund strategy shouldn’t leave you broke, either.

The relationship between return dispersion and diversification is important. In 2006, academics introduced a measurement called active share, to quantify the concept of intentionally under-diversifying relative to an index in an attempt to add value. This is how traditional active management works. Active share measures the extent a fund manager is using active management, or how much its strategy diverges from simply tracking its index.

Thus, when someone says that index funds lead to over-diversification, they are effectively saying you should invest in something less diversified, with a higher active share, so you can try to outperform the index.

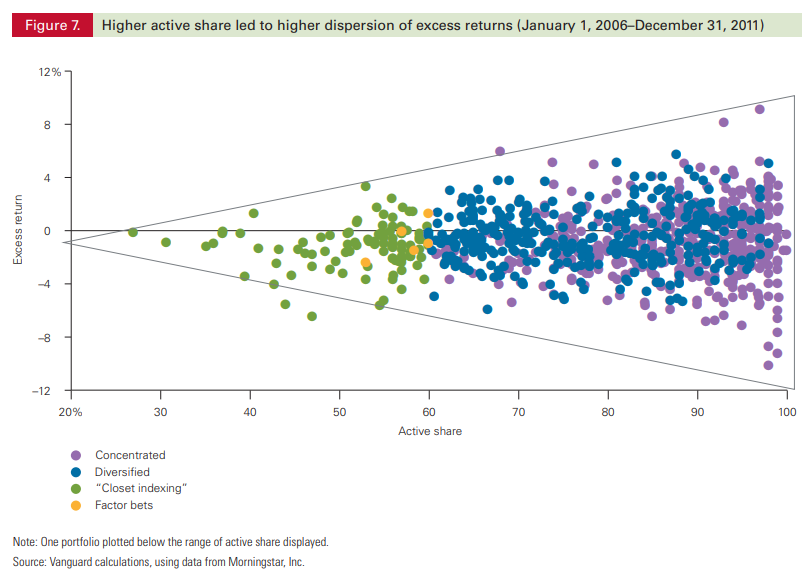

In a 2012 paper, Vanguard looked at the dispersion of outcomes for actively managed mutual funds alongside their active share. They found, as active share increases, so does the dispersion. This is exactly what we would expect to see. When you hold a subset of an index, you are likely to perform either better or worse than the index. The smaller the subset, the better or worse you’re likely to do.

A 2018 paper from Dimensional Fund Advisors took a different approach to assessing diversification. First, to discuss their findings, I’m going to pick on dividend investors for a moment. Bear with me – there’s a point.

If you remember my post on dividend growth investing, I explained that dividend growth stocks have market-beating performance on average, but it’s mostly explained by their increased exposure to the value and profitability factors – not some magical dividend fairy. This is important, because it means you can attain essential factor exposure with a diversified portfolio of dividend- and non-dividend-paying stocks, instead of narrowing your selection to dividend-paying stocks in particular.

Now, back to that Dimensional paper. In it, they took an index of 2,637 global large-cap stocks with an emphasis on the size, value, and profitability premiums. In other words, they took a global large-cap index and adjusted it to have more weight in smaller large stocks, large value stocks, and large profitable stocks. They tested this combination against the MSCI All Country World Index from 1994–2017, and found that their adjusted index beat the market index by an annualized 0.8%.

Next, they reduced the diversification in their adjusted, 2,637-stock index, to test the effect diversification would have on the reliability of this outcome. They sampled portfolios with subsets of 50, 200, 500, and 1,000 stocks, and built each sub-portfolio to contain the same average excess return and similar volatility compared to the full adjusted market index. Phrased differently, the sub-portfolios resembled the overall adjusted index from the perspective of expected returns and volatility. The main difference was their level of diversification.

After controlling for factor exposure, the power of diversification became clear. The dispersion in each sub-portfolio’s returns increased with each reduction in the number of securities held. And, as dispersion increased, the probability of beating the market decreased. The authors found a 92% probability that the full adjusted index would beat the market index over 5 years. The cloned sub-portfolio with only 50 stocks had a much lower, 63% probability of beating the market index over 5 years.

Dimensional ran this analysis in the context of their investment products, which own the market as a whole while targeting factors with higher expected returns. But their finding extends to a traditional index fund as well. Capturing the market premium similarly requires broad diversification, where more diversification increases the reliability of the outcome.

This should shed light on why a dividend investor (who is essentially a value- and profitability-factor investor in disguise), is in for a wide dispersion of potential outcomes if they hold only 20 or 30 stocks. True, they may do really well, as I know some dividend investors have. But they’re at least as likely to do really poorly. The less diversified and more concentrated the portfolio, the harder it becomes to predict actual performance.

This finding is both intuitive and profound. We know a small number of stocks tend to drive most of the market’s returns. The problem is, we cannot know in advance which small number are going to be the winning ones, or when. Without the ability to predict the future, evidence suggests you’re best off holding all of the stocks in the market, to get an outcome similar to what the market has to deliver.

This also tells us very clearly, if a reliable outcome is your investment goal, there is no such thing as over-diversification.

I mentioned that we know empirically that a small subset of stocks drives most of the market’s returns. In a paper originally drafted in 2017, Hendrik Bessembinder found that nearly 58% of common stocks in the U.S. have underperformed the Treasury bill rate over their full lifetime, and the entire gain in the U.S. stock market since 1926 is attributable to only 4% of its stocks.

In a paper originally drafted in 2015, J. B. Heaton, Nick Polson, and Jan Witte created a simple model to illustrate why this matters. Let’s say we have an index consisting of five securities. Over a given time period, four of them return 10% while the fifth one returns 50%. If an active manager decides to create a portfolio using an equally weighted subset of one or two of the available securities, there will be 15 possible actively managed portfolios they could construct, with these possible outcomes:

In this example, the mean average return of all active fund managers will be 18%, while the median return for the active managers will be 10%. Two-thirds of the actively managed portfolios will underperform the index by omitting the security that returns 50%, which is always included in the index. The index portfolio containing all of the stocks will return 18%. The surest way to avoid the relatively likely bad outcome of the active managers is to hold all of the stocks in the index.

So what are your key take-aways from today’s post?

If your goal is a reliable outcome, which seems like a sensible goal for any long-term investor, I do not think that index funds are over-diversified. Has anyone ever told you otherwise? Tell me how you responded. You can also tune into weekly episodes of the Rational Reminder Podcast wherever you get your podcasts.