If you’ve ever planned for retirement, you’ve probably heard of the famous 4% rule. This guideline suggests you can safely spend 4% of your portfolio in your first year of retirement, adjusting that amount for inflation each year, without running out of money.

But here’s the problem: the 4% rule relies heavily on optimistic, biased historical data. New research paints a more conservative—and perhaps more realistic—picture. The safer withdrawal rate may be much closer to 2.7%.

In this post, we’ll unpack why 2.7% is the new 4% for retirees and what this means for your long-term plans.

In 1994, financial planner William Bengen tested historical returns of US stocks and bonds over 30-year periods. He found that a 4% withdrawal rate was the highest spending rate that did not result in failure throughout his historical simulations.

Since then, this advice has been widely adopted. A review of 50 popular personal finance books shows many of them recommend a 4%, or higher, spending rule.

The US has historically enjoyed unusually strong stock returns—so strong that economists call it the equity premium puzzle. The US avoided major disasters that devastated other markets (like losing wars on home soil), and investors were rewarded for that good fortune.

A 2022 study, Is The United States A Lucky Survivor: A Hierarchical Bayesian Approach, estimated that US stock returns exceeded expected premiums by 2%, thanks to luck and optimism about avoiding future catastrophes. Relying on this exceptional past performance assumes that the future will bring equally favorable outcomes—a risky bet.

A more comprehensive study, The Safe Withdrawal Rate: Evidence from a Broad Sample of Developed Markets, looked at 2,500 years of returns across 38 developed countries. This dataset includes markets that performed poorly or even failed altogether.

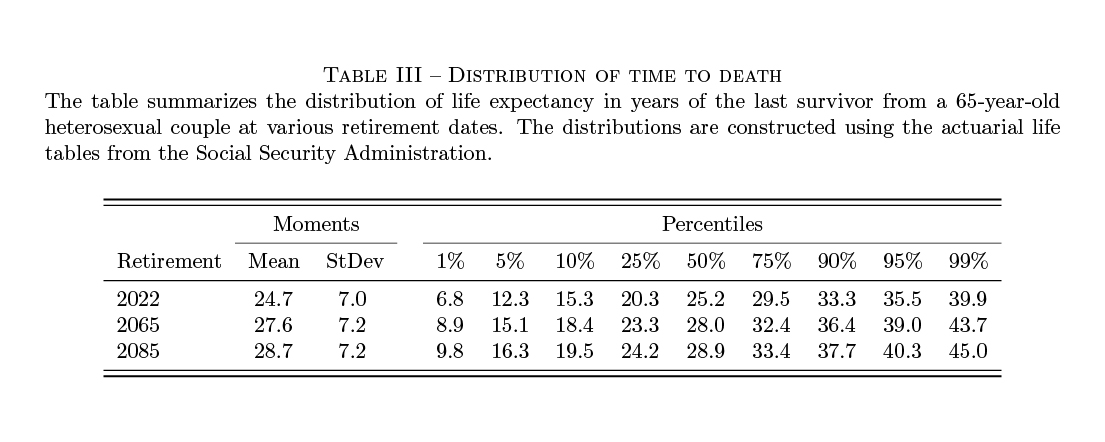

Instead of using a fixed 30-year retirement period, researchers accounted for actual life expectancies, using Social Security mortality tables. For a 65-year-old couple today, average retirement lasts nearly 25 years—but there’s a real chance it could stretch to 35 years or more.

Source: Anarkulova, Aizhan and Cederburg, Scott and O’Doherty, Michael S. and Sias, Richard W., The Safe Withdrawal Rate: Evidence from a Broad Sample of Developed Markets (September 22, 2022).

Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4227132 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4227132

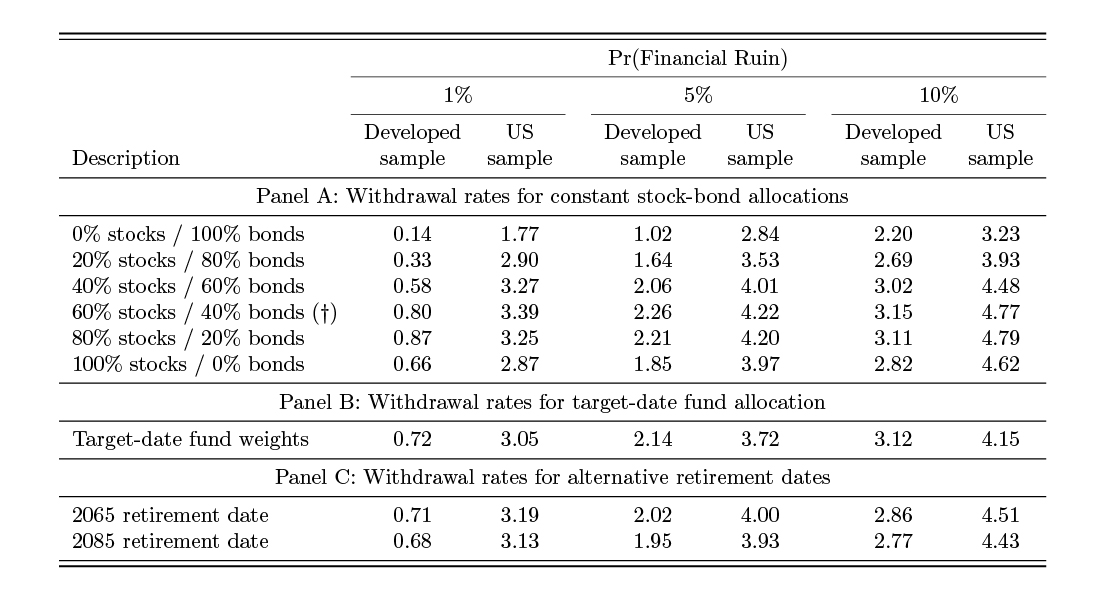

For a retiree with a traditional 60% domestic stock / 40% bond portfolio:

Not reported in the paper, adding international diversification improves these numbers:

However, if you expect to live longer—like Canadian retirees (who live longer than Americans) or younger generations today planning for life to 2085—the sustainable rate drops closer to 2.7%.

Source: Anarkulova, Aizhan and Cederburg, Scott and O’Doherty, Michael S. and Sias, Richard W., The Safe Withdrawal Rate: Evidence from a Broad Sample of Developed Markets (September 22, 2022).

Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4227132 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4227132

The takeaway is simple: the widely used 4% rule isn’t realistic for many retirees. Longevity risk and global market volatility mean a lower withdrawal rate is safer.

It’s also clear that international diversification significantly improves outcomes, reducing the odds of outliving your money.

Beyond Withdrawal Rules

Here’s some good news: most retirees won’t rigidly stick to a single withdrawal rate. Spending often naturally declines over time, especially after accounting for inflation.

Other strategies can further protect your retirement:

While 2.7% may seem conservative, it’s a much more realistic starting point for planning.

Historical US returns were exceptional, but luck isn’t a strategy. Using a broader sample is the best way to set expectations for the future.

The result may seem overly conservative, but this speaks to a problem with safe withdrawal rates, not with the data. They are designed to sustain spending even in the worst-case historical scenario.

They do not adapt to whatever scenario you happen to live through. A more flexible approach that varies spending over time based on your realized and expected returns likely increases overall sustainable spending without increasing the risk of running out of money. That, combined with strategically drawing from government benefits like CPP and OAS, is the approach taken by financial planners at PWL.